Introduction

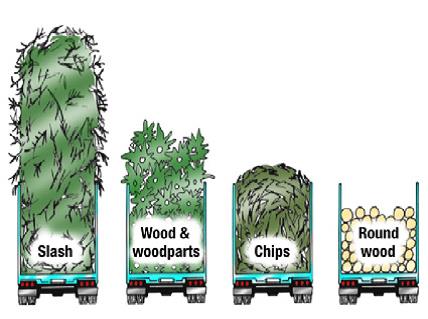

One challenge associated with transporting woody biomass for energy and bio-based products is that woody biomass in its raw form (e.g. slash, un-delimbed small trees and tree sections) has a low bulk density (1). Low bulk density increases the cost of transportation because air is a major component of the transported volume. In addition, the complex texture of the material makes handling technically difficult. Bulk density may be increased and the problems associated with the material’s texture reduced by compaction or by comminution via chipping, grinding or shredding. However, processing biomass feedstock into small pieces may introduce new problems by decreasing durability and longevity during storage (Figure 1). Transport and delivery are key elements of forest activities. The way they are organized can have implications for the production system as a whole.

Figure 1. Volume Differences of the same Weight Material by Different Product Types

Woody biomass feedstock for energy can be delivered to forest products manufacturing facilities by truck or rail. However, rail is rarely used in the southeastern United States. Trucks are used almost exclusively and the exact configuration can take several forms that vary based on the combination of truck and trailer. The manner in which the biomass is pre-processed at the logging site often determines the transportation configuration. This fact sheet provides a brief description of the various configurations of trucks and trailers available for biomass transport.

Trucks

Trucks transport most forestry products and harvesting material. About 90 percent of the pulpwood delivered to U.S. mills in 2005 arrived by truck (2). Trucks for transporting forest commodities are either tractor-trailer or fixed truck type.

Tractor-trailers. Most goods in the South are currently transported in 80,000-lb. gross vehicle weight (GVW) road tractor-trailer combinations (tare weight, or the weight of the container and/or packing materials without the weight of the goods it contains, to tractor-trailer is usually 26,000 lbs). These combinations use standard highway road tractors, six- to ten-wheel tandem axle highway trucks with either a conventional (i.e. engine in front of compartment) or cab-over-engine design. Typical road tractors weigh about 12,000 to 20,000 lbs., and can include sleeping compartments and provisions for hydraulic power for trailer functions such as operating self-unloading floors. Road tractors are designed to pull cargo trailers. These trucks are designed for greater capacity and offer the versatility of changing the type, size, and configuration of cargo space.

Fixed trucks. Fixed trucks have a cargo area integral to the operator cab and chassis. Fixed trucks are generally less than 40 feet long with a payload capacity less than road tractors. Fixed trucks are usually shorter than road tractor-trailer combinations, and allow more maneuverability in tighter areas. Because of the lower payload capacity, fixed trucks work best when hauling distances are shorter.

Trailers

There are several trailer options available when it comes to hauling woody biomass.

Log trailers. The log or bunk type of trailer is designed to haul trees, poles, or shortwood in racks. They are lightweight and subsequently can have high payload capacities. Most require unloading equipment at the receiving facility, although some are modified to drop one side of the log restraints and allow a front loader to push the load off one side of the trailer. Bundled material can also be transported in these types of trailers (Image 1).

Image 1. Log Trailer source: USDAForest Service, www.forestryimages.org

Container trailers. Container trailers are designed to hold bulk material and the container is designed to be handled full. Because of this, they are built with sturdy walls and supports and their total capacity in cubic volume is less than bulk vans or log trailers. They can be left on a site and filled as desired and then removed and replaced with an empty container at the same time. They can also be used as storage at the end user’s site. In addition, container trailers may be more suitable for collecting yards where road access is limited or where smaller volumes are present (Image 2).

Image 2. Container Trailer source: Tat Smith, University of Toronto

Container trailers handle most of the international trade material moved by truck from ship ports, and a large portion of the collected solid waste in the U.S. These consist of a trailer chassis with a removable cargo container or box. The containers can vary in size, construction and volume, and the chassis can have the capacity to load and unload containers. Two common varieties are roll-off trucks and containers commonly used to collect and haul solid waste, as well as container trailers to distribute goods from ships.

Vans. Bulk vans, also known as chip vans, transport forest products. They are enclosed box trailers generally 8 to 8.5 feet in width and 12 feet or less in height when pulled by a road tractor. Bulk vans have either an open end or an open top. The difference between the box trailers seen on most highways and vans hauling harvesting products (i.e. bulk vans) is that most box trailers are built for containerized cargo (i.e. commodities in boxes or on pallets) (Image 3).

Image 3. Chip Van source: Rien Visser, Virginia Tech

Open-top bulk vans are usually loaded with front wheel loaders from the side, or from overhead bins. These must have removable tarps to comply with most state regulations. Open-end bulk vans are generally used for chippers, and must have tailgates that both allow loading and reduce or eliminate flying material while in transit.

Bulk vans used in the South typically have a maximum capacity of 80,000 lbs. Depending upon the weight of the road tractor and the trailer itself, this means that they can carry a legal payload of about 42,000 to 52,000 lbs. The cubic yard capacity of the trailer is matched to the material being hauled. To achieve the maximum weight capacity for lighter material, the bulk van must have more volume capacity. Most bulk vans carry between 97 and 131 cubic yards, although specialty chip vans for extremely light material (e.g. planer shavings) can hold 150 cubic yards or more. Bulk vans are often used for hauling garbage and debris, although bulk vans for this purpose have stronger walls and floors, and usually lower cubic volume capacity.

Bulk vans can be unloaded by placing them on a tipping platform, raising the front of the trailer and unloading the contents from the rear. In the southern region or in areas without major biomass facilities, bulk vans increasingly have integral hydraulically-operated self-unloading floors (or live floors) that move the contents from inside the trailer to the rear and out of the tailgate. The advantages of these trailers are that they 1) do not require a truck unloading platform at the destination, 2) can place material within any area of the storage yard, 3) can unload unacceptable loads at a different location, and 4) can back haul other material on the return trip to places without truck unloading platforms. However, live floor bulk vans are heavier than regular bulk vans, and this reduces the potential legal weight capacity of the payload.

Summary and Conclusions

The tractor-trailer/bulk van combination is generally considered to be the most cost-efficient mode of transporting woody biomass in the South. This configuration is feasible because of the relatively straight roads in the South. It is cost efficient because of the bulk van’s high payload capacity and relatively low weight. Atractor-trailer/container trailer combination may be more appropriate if the woody biomass were being transferred from transport by truck to transport by rail or boat because the containers containing the biomass could literally be lifted from the truck to the train or boat. Fixed trucks with enclosed beds may be more appropriate where longer trucks have trouble negotiating frequent turns.

Endnotes

1 Hakkila, P. 1989. Utilization of residual forest biomass. Berlin: Springer: 568 p.

2 Forest Resources Association. 2006. Annual Pulpwood Statistics Summary Report 2001-2005. Publication 06-A-7.